Fixing the Macro to Solve the Micro: What Canadians Really Think About Growth

New polling on what Canadians think about economic growth messages

Earlier today, I released new polling from Abacus Data that tries to answer a question I’ve been thinking a lot about lately: how do Canadians react to the evolving economic and political narrative being shaped by the Carney government?

Since becoming Prime Minister, Mark Carney has put economic growth at the centre of his vision for the country. He’s made it clear that productivity, competitiveness, and business investment aren’t just abstract metrics—they’re meant to be the tools we use to tackle the affordability crisis, improve public services, and restore a sense of fairness. It’s a reframing of economic ambition that I’ve come to call fixing the macro to solve the micro.

It’s a smart and necessary shift. But will it resonate with Canadians? Do they believe that economic growth will lead to better lives?

That’s the question we set out to answer.

We surveyed over 2,500 Canadians to understand whether people see a connection between economic growth and their personal well-being. The results show that while many are open to the idea, there’s still a long way to go before a pro-growth agenda becomes a broadly supported national project.

Let’s start with the good news: 61% of Canadians agree that improving Canada’s economic performance through productivity, GDP growth, or business investment—would improve their personal standard of living. Just 6% disagree. That’s a promising foundation.

But look a little closer and the picture becomes more complicated. Nearly 4 in 10 are either unsure or skeptical. And when we asked whether people believe that governments, when they talk about economic growth, are actually referring to things that will help them, only 47% said yes. In fact, 52% of Canadians agree with the statement: Even if the economy grows, I don’t trust that the benefits will reach people like me.

That’s the core challenge. The problem isn’t growth - it’s belief in inclusive growth.

The reasons for that skepticism are revealing. Many of those who don’t think growth will help them are on fixed incomes or retired. Others feel the system is rigged, or that past growth hasn’t led to lower costs or better services. Some just don’t trust that government decisions are made with them in mind.

This is the emotional terrain that economic messaging must navigate. Especially now, when so many Canadians feel stuck or squeezed, the promise of growth has to come with proof.

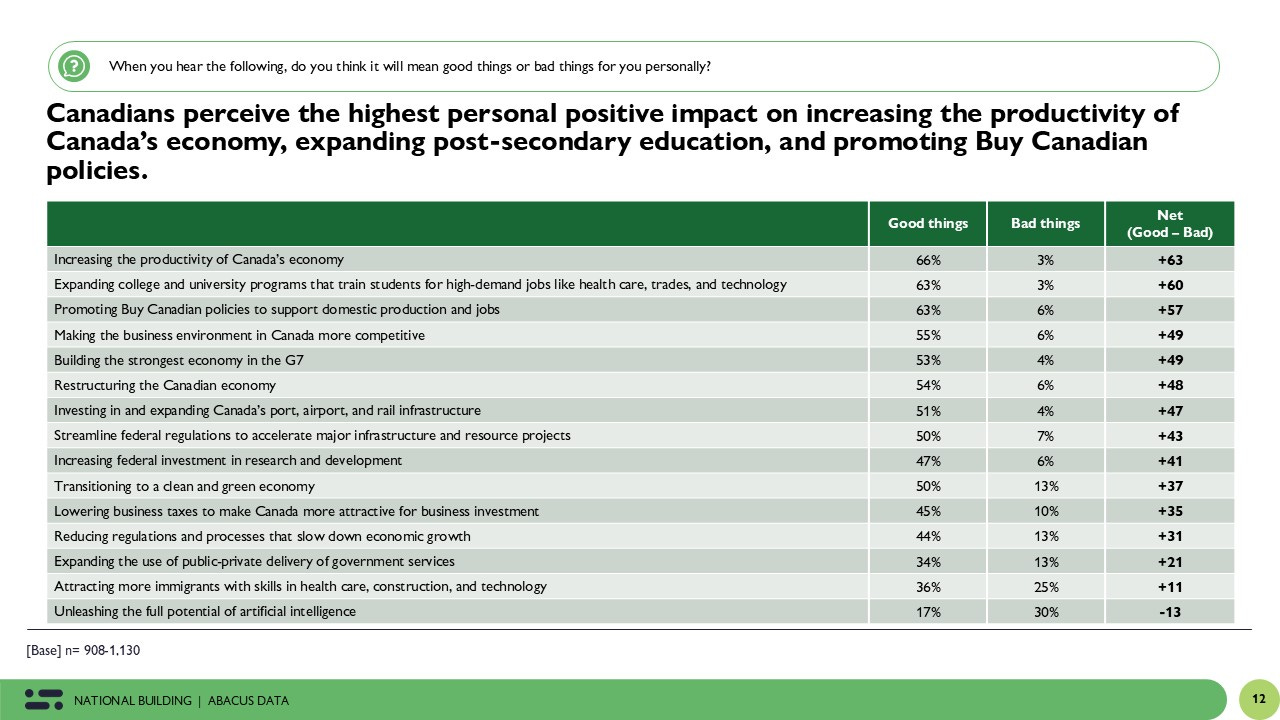

To better understand what kind of economic messages resonate, we tested a series of outcomes and asked Canadians whether they would mean “good things” or “bad things” for them personally.

At the top of the list? Increasing productivity (66% good), expanding post-secondary training for in-demand jobs (63%), and promoting Buy Canadian policies (63%). These ideas are tangible, practical, and rooted in fairness and national pride. They connect macro-level ambition with the day-to-day concerns people care about most.

But not everything landed as well.

Support for ideas like restructuring the economy or making Canada more competitive was still strong—but softer. And support dropped significantly when we tested more contentious ideas: attracting more skilled immigrants (+11 net positive), expanding public-private partnerships (+21), and unleashing artificial intelligence, which had a net negative score of -13. Just 17% said AI would be good for them personally. Thirty percent said it would be bad.

That last number should be a wake-up call. Canadians are deeply unsure about AI not just because of the technology itself, but because they don’t yet see how it helps them. For many, it symbolizes job loss, inequality, and a future they feel shut out of.

Even when it comes to messages that were central to the Carney campaign like building the strongest economy in the G7 support isn’t universal. While 53% say that would be good for them personally, 43% say they’re unsure or that it wouldn’t help them. Support is strongest in Alberta, B.C., and among men and older Canadians. It’s weaker among women, Quebecers, and those aged 30 to 44.

That tells us something important: economic messages work best when they feel real, local, and lived. Canadians don’t experience “the economy” in the abstract. They experience it through housing costs, school fees, healthcare wait times, and whether there’s a good job nearby.

If the Carney government - or anyone else - wants to bring Canadians along with a growth agenda, they need to meet people where they are. They need to show how growth lowers bills, funds schools, builds hospitals, and makes life more secure, not just more efficient.

The good news is Canadians aren’t opposed to growth. But they are cautious. They’ve heard big promises before. Now, they want to know: will this help me?

That’s the challenge. But it’s also the opportunity. Because if we can bridge that gap, if we can show that the macro truly does fix the micro, we can build something far more durable than GDP gains. We can build trust. And that might be the most important economic asset of all.