A Big Energy Deal with a Small Political Impact: What Canadians Really Think of the Canada–Alberta MOU

How are Canadians reacting to last week's Canada-Alberta MOU

The Canada Alberta energy agreement arrived in a political moment defined by more questions than answers. Whenever a federal government announces a major shift on energy or climate policy, three tests follow immediately. First, do Canadians support the substance of the decision or does it trigger backlash. Second, does the move strengthen or weaken the prime minister who signed it. Third, does it shift the broader political landscape by either sharpening partisan divides or softening them.

These are the questions our rapid Abacus Data poll (we can work fast) was designed to answer. We went into field less than twenty four hours after Ottawa and Alberta signed their memorandum of understanding on energy and climate policy.

The agreement includes approval for a new oil pipeline to the West Coast, a pause on clean electricity rules in Alberta, and a renewed commitment to net zero by 2050. The announcement produced immediate reactions from premiers, Indigenous leaders, environmental groups, and opposition parties.

Yet early elite reaction does not always align with public opinion. Sometimes the public moves quickly, sometimes it waits to be persuaded, and sometimes it simply shrugs.

So we asked Canadians what they made of the deal. We tested awareness. We probed support for the pipeline and for the major components of the agreement. We asked how the deal shapes perceptions of Mark Carney’s leadership and whether it shifts impressions of Pierre Poilievre, Danielle Smith, David Eby, or Steven Guilbeault. Most importantly, we examined whether any of this has altered the political terrain Canadians will be standing on.

The short answer is that not much has moved. Vote intention is stable. Leader impressions are predictable. Approval of the Carney government is unchanged. But beneath that surface level stability is a story about how public opinion is organising around the next phase of Canada’s energy and climate debate.

What we learned

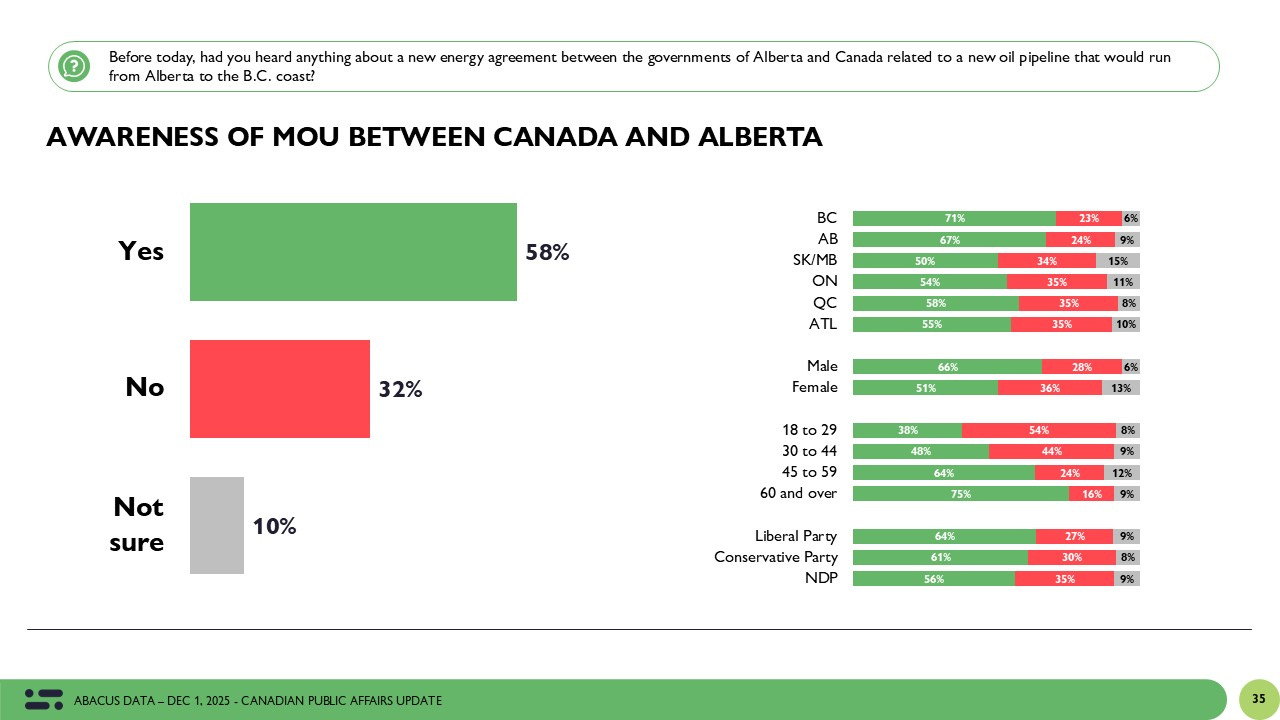

Given how quickly we went into field, awareness of the Canada Alberta MOU is relatively strong. Almost 6 in 10 Canadians say they have heard about the agreement. Awareness is highest where you would expect it to be: Alberta, British Columbia, and among older Canadians who tend to follow politics more closely.

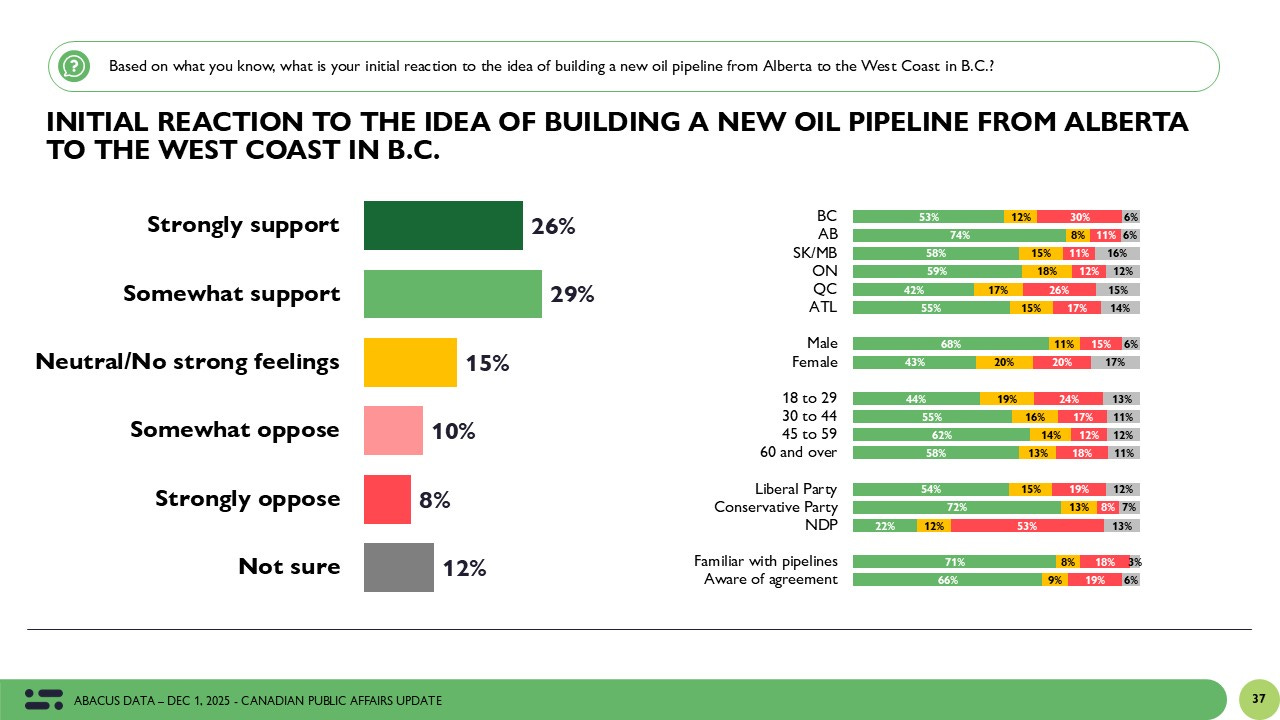

When we strip away the partisan noise and ask directly about a new pipeline from Alberta to the West Coast, the public is more open to the idea than the political debate suggests.

Nationally, 55 percent say they support the idea of a pipeline to the West Coast, while only 18 percent are opposed. Support is overwhelming among Alberta respondents and Conservative voters, but it is not confined to them. Support outpaces opposition among 2025 Liberal voters by roughly two to one. In every region of the country, more people support than oppose the concept.

Even in British Columbia, where opposition is often presumed to be overwhelming, 53 percent support the idea while 30 percent are opposed. The more interesting story is inside the provincial party coalitions. Among BC NDP supporters, 37 percent support a pipeline while 47 percent are opposed. Among BC Conservatives, support hits three quarters.

That gap inside the BC NDP coalition looks more like a hairline fracture than a full split, but it is real and it runs directly through David Eby’s base.

This pattern repeats in Alberta. Among UCP voters, support for the pipeline is almost unanimous. But a majority of Alberta NDP voters are also on side. The political class is divided along classic partisan lines. The public is more fluid.

It also matters that the deal is about more than a pipe in the ground. Elements such as a carbon capture pipeline, Indigenous co ownership, and a commitment to net zero by 2050 all generate more support than opposition. Even the more contentious ideas, like easing the tanker ban or pausing clean electricity rules, tend to produce ambivalence rather than outrage.

In short, the package looks like a compromise that many Canadians can live with. That does not mean it is risk free. It does help explain why the initial reaction has been relatively soft.

Carney’s pragmatism test

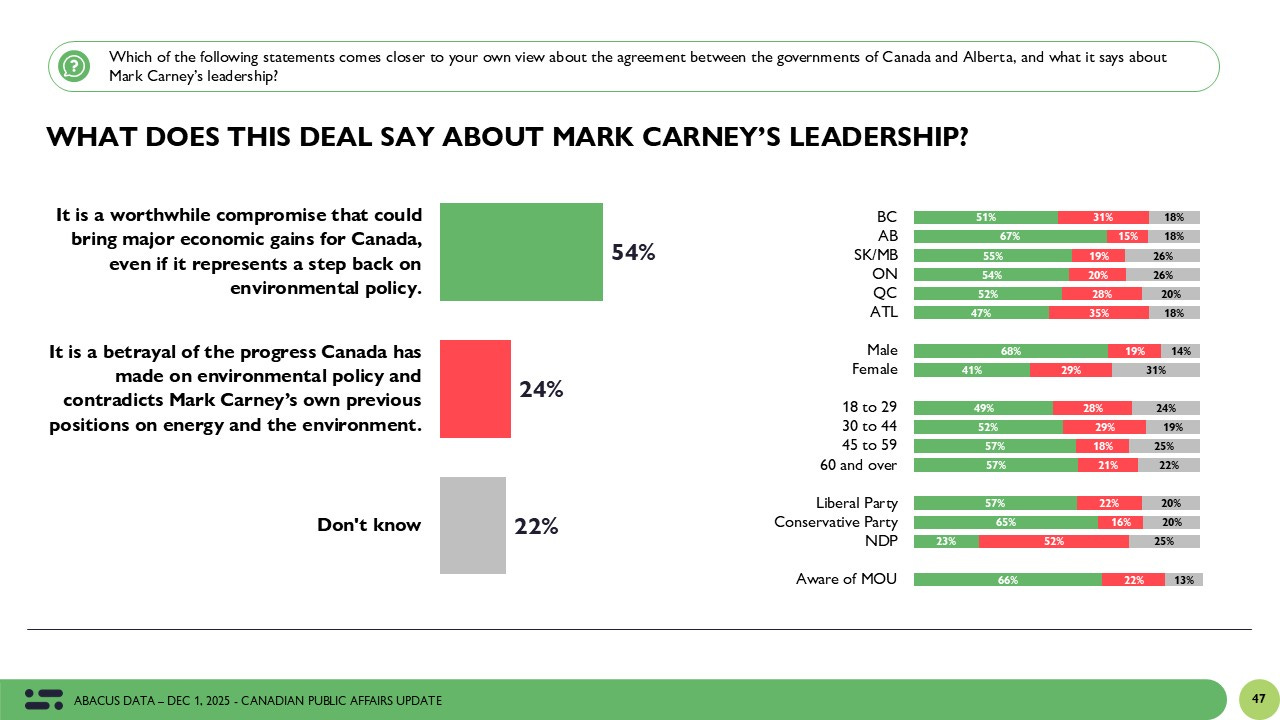

If this agreement is a test of Mark Carney’s leadership, most Canadians are marking it in the “pragmatic compromise” column, not the “sellout” column.

More than half of Canadians say the deal looks like a worthwhile trade off that could deliver economic benefits, even if it means walking back some environmental commitments. That view is strongest in Alberta, but it is not confined there. Among those who are familiar with the MOU, two thirds see it as a reasonable compromise.

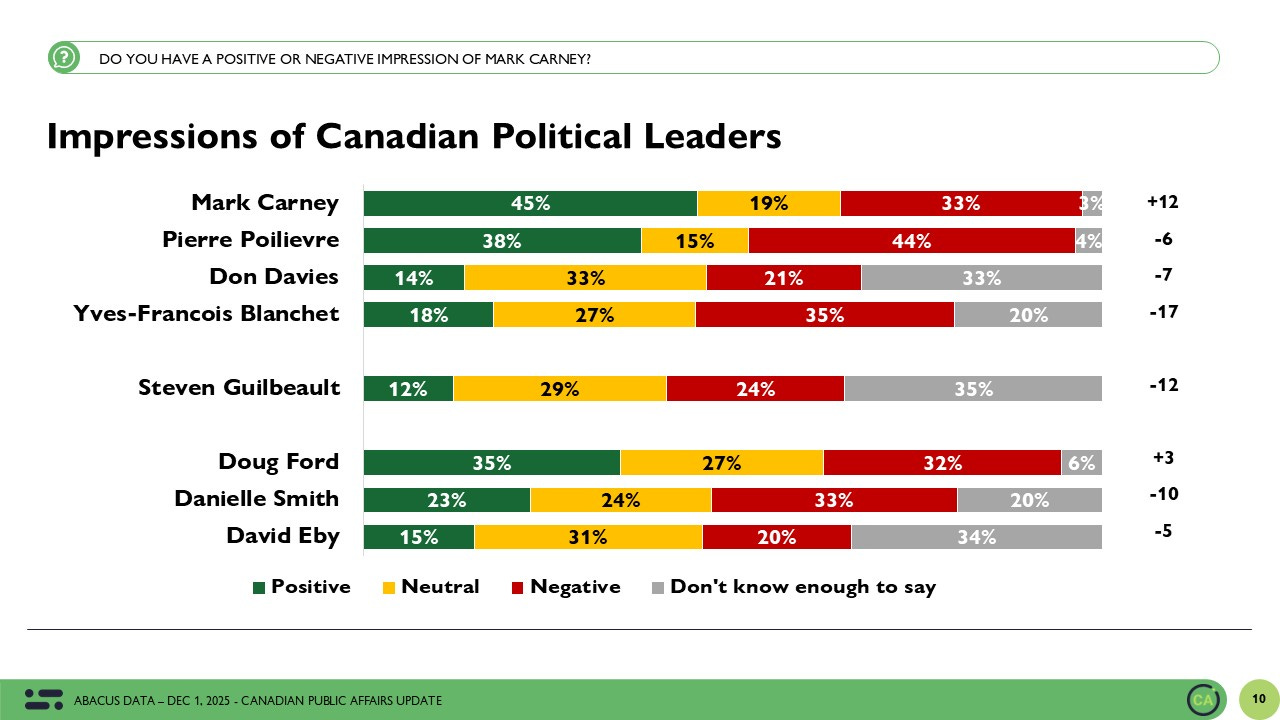

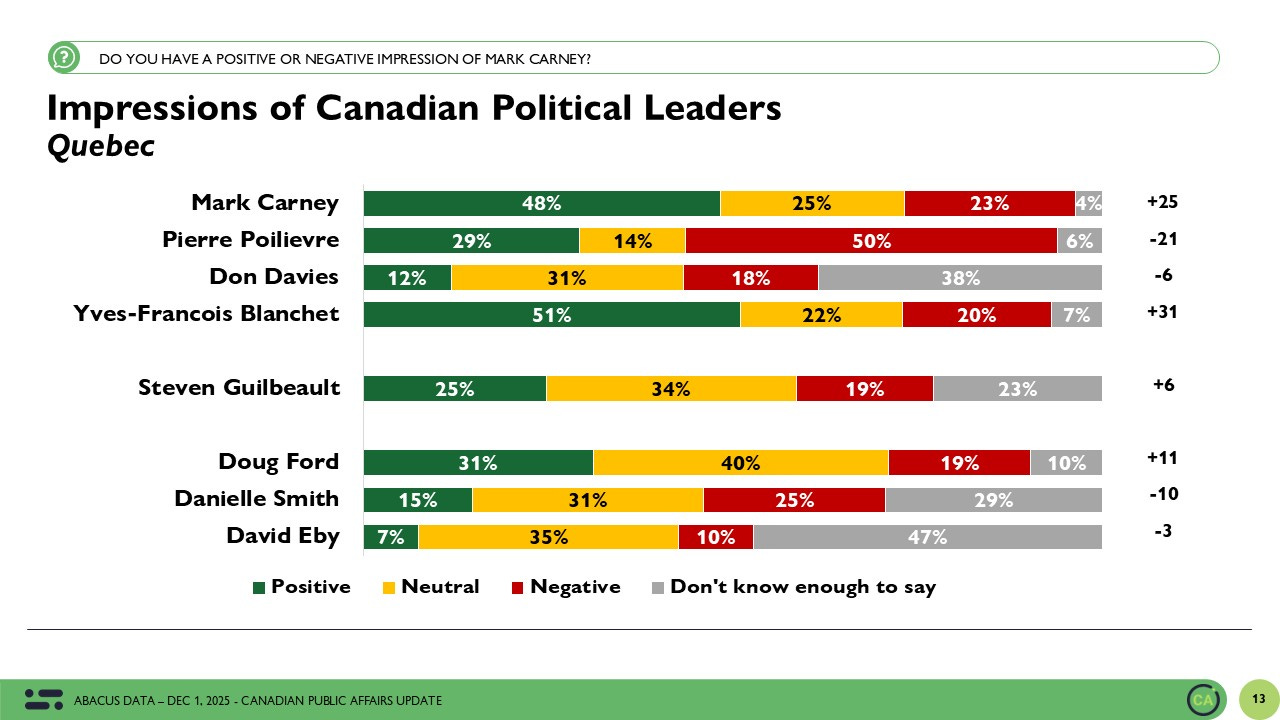

Carney’s personal numbers remain solid. Nationally, his net impression sits at plus 13. He is strongly positive in Quebec and Ontario and modestly positive in British Columbia, even though his negatives have ticked up in that province. In Alberta, he is still underwater, but his favourables have risen since our last survey.

Among 2025 Liberal voters, support for the pipeline initiative is broad. When framed in terms of jobs and energy security, nearly 7 in 10 say that argument makes them more likely to back the project. A majority say the decision shows leadership and pragmatism.

The risk is not absent. About 1 in 5 Liberal voters see the deal as a betrayal of environmental values. That is not enough to shatter the coalition, but it is enough to worry any leader who understands how fragile trust can be when parties move toward the centre on a deeply symbolic issue.

For Poilievre, the numbers are more static than dramatic. His net impression remains negative nationally, but he continues to enjoy strong support in Alberta and parts of the Prairies. If the MOU threatened his claim to be the only authentic champion of pipelines and energy development, it does not show up in this data. Conservative voters are likely waiting to see whether Carney’s move is a one off, or an attempt to permanently occupy more of the “pro development” lane.

Danielle Smith, meanwhile, appears to have banked a rare intergovernmental win with limited downside. Alberta voters like the deal, like the pipeline, and like the economic story that comes with it. On this file, she is playing at home.

The toughest position belongs to David Eby. When British Columbians are told about jobs and Indigenous economic benefits tied to the pipeline, almost two thirds say they are at least somewhat supportive. Yet when we test changes to the tanker ban and the fact that BC was excluded from the agreement, support drops. A majority oppose loosening the tanker ban. Almost half say BC’s absence from the deal makes them less likely to support it.

Eby is defending a coast that does not want more tanker traffic, while many of his own voters are open to the jobs and investment a pipeline might bring. Ottawa can claim to be balancing climate and economic goals. Victoria is left explaining why the province is out of the room.

Guilbeault, climate, and what Canadians really worry about

Steven Guilbeault’s resignation is the most dramatic political act associated with the MOU so far. Our data suggests it has not yet become a dramatic public moment.

Only one quarter of Quebecers have a positive view of him. Outside Quebec, his brand is weak or negative. Nationally, his net impression sits at minus 12, well behind Carney, Poilievre, and even Danielle Smith. In Alberta, his numbers are hostile.

There is no sign yet that his departure has damaged the Carney government in Quebec, where the Liberals maintain a lead over the Bloc similar to what we measured before the deal. Only about one in five Canadians say the MOU represents a betrayal of climate values.

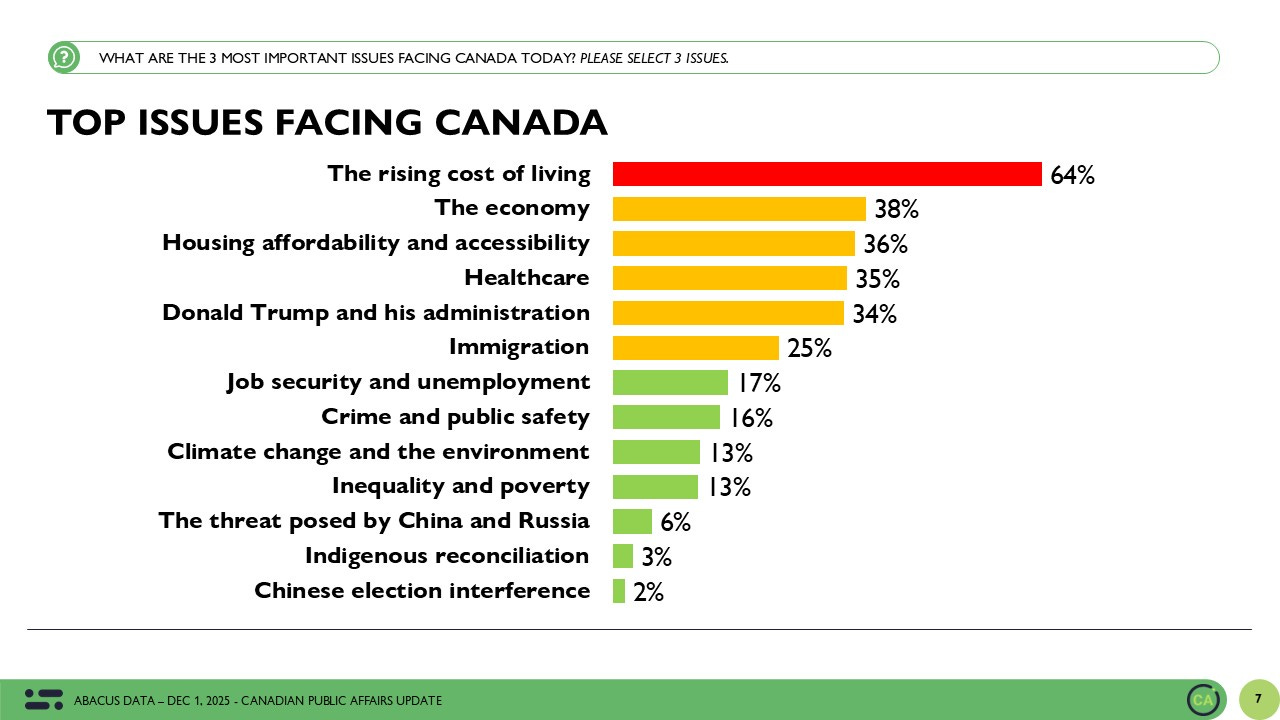

The more important context is the issue agenda. Climate change makes the top three list of national concerns for only 13 percent of Canadians. The cost of living, housing, and health care dominate. In that environment, even a significant shift in climate posture can be absorbed if people believe it helps with jobs, affordability, or energy security.

At the same time, most Canadians tell us they do not see a simple trade off between energy development and climate ambition. A clear majority believes Canada can be a leader on energy and still meet its climate goals. That belief is strongest in Alberta and among Liberal voters, but it is present even in Quebec.

The political space for a “both and” agenda exists. The question is whether events, implementation, and future crises will narrow it.

A calm surface over shifting ground

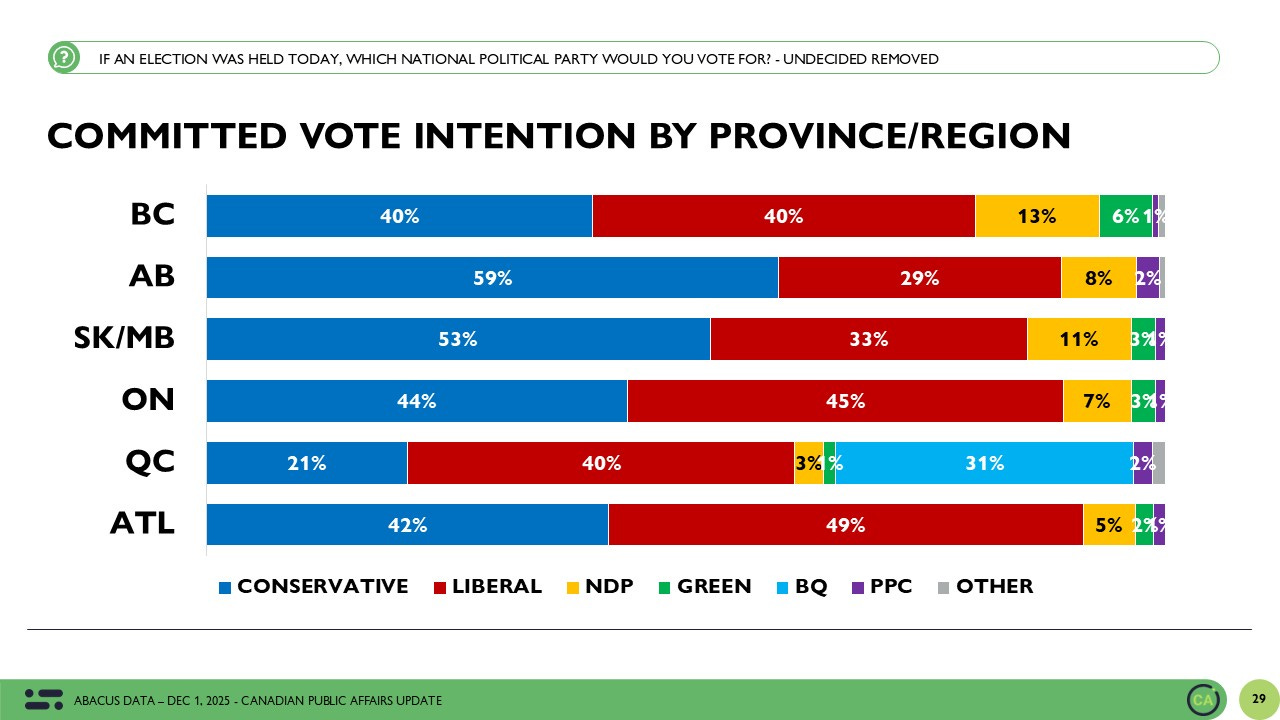

So far, the Canada-Alberta energy MOU has not changed the game. Vote intention remains essentially tied between Liberals and Conservatives. Approval of the Carney government is steady. Leader impressions are mostly where they were before the news broke.

For the government, that is a short term victory. They moved on a file that has toppled leaders and divided parties before, and emerged without an immediate backlash.

For their opponents, the deal has not yet produced a wedge sharp enough to cut into the Liberal coalition.

The deeper story is about where the risks are building. In British Columbia, tanker politics and provincial exclusion could bruise both federal Liberals and the provincial NDP. In Quebec, Carney’s strong personal brand may protect the government for now, but a reinvigorated Bloc could try to turn this into a test of environmental authenticity. Among progressives and younger voters, the cumulative effect of compromises like this will shape whether they see Carney as a trustworthy climate leader or as another manager of decline.

The next rounds of polling will tell us whether this remains a contained compromise or the opening chapter of a larger realignment in how Canadians think about energy and climate. For the moment, the numbers say equilibrium. The politics of it feel less settled.